OxCARRE associate

Rabah Arezki and

Maurice Obstfeld from the IMF, and also available on the IMFDirect blog

here, write on

The Price of Oil and the Price of Carbon

By

Rabah Arezki and

Maurice Obstfeld

“The human influence on the climate system is clear and is evident from the increasing greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere, positive radiative forcing, observed warming, and understanding of the climate system.” —

Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, Fifth Assessment Report

Fossil fuel prices are likely to stay “low for long.” Notwithstanding important recent progress in developing renewable fuel sources, low fossil fuel prices could discourage further innovation in and adoption of cleaner energy technologies. The result would be higher emissions of carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases.

Policymakers should not allow low energy prices to derail the clean energy transition. Action to restore appropriate price incentives, notably through corrective carbon pricing, is urgently needed to lower the

risk of irreversible and potentially devastating effects of climate change. That approach also offers fiscal benefits.

Low for long

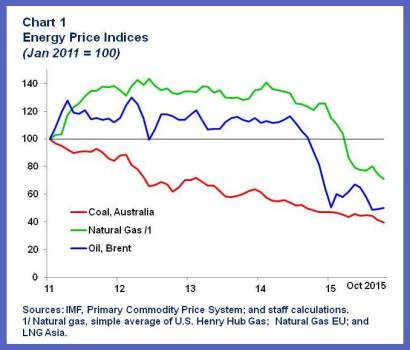

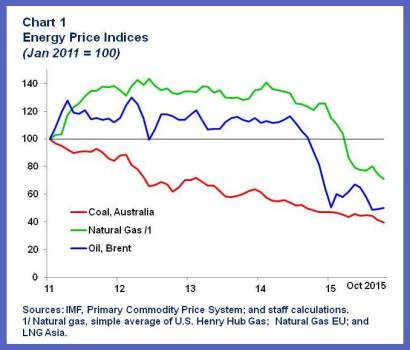

Oil prices have dropped by over 60 percent since June 2014 (see Chart 1). A commonly held view in the oil industry is that “the best cure for low oil prices is low oil prices.” The reasoning behind this adage is that low oil prices discourage investment in new production capacity, eventually shifting the oil supply curve backward and bringing prices back up as existing oil fields—which can be tapped at relatively low marginal cost— are depleted. In fact, in line with

past experience, capital expenditure in the oil sector has dropped sharply in many producing countries, including the United States. The dynamic adjustment to low oil prices may, however, be different this time around.

Oil prices are expected to remain lower for longer. The advent of shale oil production, made possible by hydraulic fracturing (“fracking”) and horizontal drilling technologies, has added about 4.2 million barrels per day to the crude oil market, contributing to a global supply glut. Shale oil will lead to shorter and more limited oil-price cycles. Indeed, shale requires a lower level of sunk costs than conventional oil, and the lag between first investment and production is much shorter. Furthermore, shale is still at a relatively early stage of its industry life cycle, where the scope for learning is substantial, as shown by production levels that have proven resilient thanks to phenomenal efficiency gains forced by the big drop in oil prices.

In addition,

other factors are putting downward pressure on oil prices: change in the strategic behavior of the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries, the projected increase in Iranian exports, the scaling down of global demand (especially from emerging markets),

the secular drop in petroleum consumption in the United States, and some displacement of oil by substitutes. These likely persistent forces, like the growth of shale, point to a “low for long” scenario, even after the supply legacy left by the high-price era of the 2000s has dissipated. Futures markets, which show only a modest recovery of prices to around $60 a barrel by 2019, support this view.

Natural gas and coal—also fossil fuels—have similarly seen price declines that look to be long-lived. Coal and natural gas are mainly inputs to electricity generation, whereas oil is used mostly to power transportation, yet the prices of all these energy sources are linked, including through oil-indexed contract prices. The North American shale gas boom has resulted in record low prices there. The recent discovery of the giant Zohr gas field off the Egyptian coast will eventually have repercussions on pricing in the Mediterranean region and Europe, and there is significant development potential in many other locales, notably Argentina. Coal prices also are low, owing to oversupply and the scaling down of demand, especially from China, which burns half of the world’s coal.

Renewables at risk

Technological innovations

Renewables at risk

Technological innovations have unleashed the power of renewables such as wind, hydro, solar, and geothermal. Even Africa and the Middle East, home to economies that are heavily dependent on fossil fuel exports have enormous potential to develop renewables. For example, the United Arab Emirates has endorsed an ambitious target to draw 24 percent of its primary energy consumption from renewable sources by 2021.

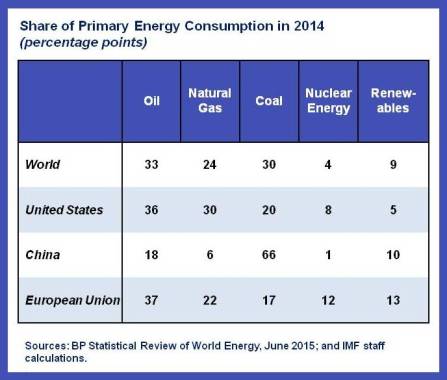

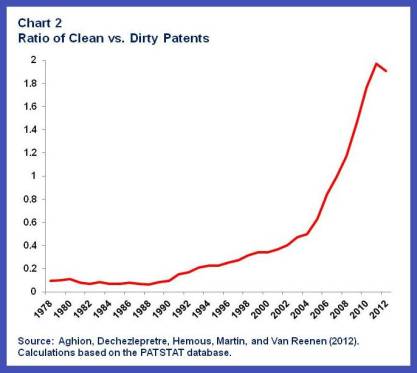

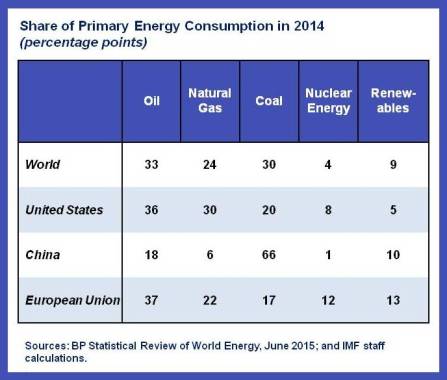

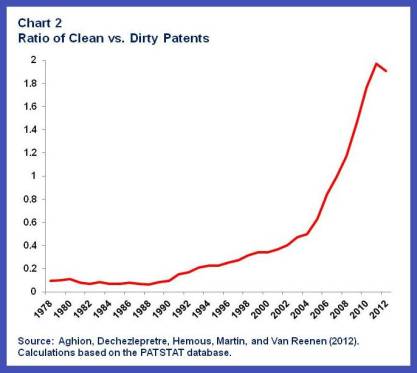

Progress in the development of renewables could be fragile, however, if fossil fuel prices remain low for long. Renewables account for only a small share of global primary energy consumption, which is still dominated by fossil fuels—30 percent each for coal and oil, 25 percent for natural gas (see Table). But renewable energy will have to displace fossil fuels to a much greater extent in the future to avoid unacceptable climate risks. Unfortunately, the current low prices for oil, gas, and coal may provide scant incentive for research to find even cheaper substitutes for those fuels. There is strong evidence that both

innovation and

adoption of cleaner technology are strongly encouraged by higher fossil fuel prices. The same is true for new technologies for mitigating fossil fuel emissions.

The current low fossil-fuel price environment will thus certainly delay the energy transition. That transition—from fossil fuel to clean energy sources—is not the first one. Earlier transitions were those from wood/biomass to coal in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, and from coal to petroleum in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. One important lesson is that these transitions take a long time to complete. But this time we cannot wait.

We owe to electric lighting the fact that there are still whales in the sea. Unless renewables become cheap enough that substantial carbon deposits are left underground for a very long time, if not forever, the planet will likely be exposed to potentially catastrophic climate risks.

Some climate impacts may already be discernible. For example, the United Nations Children’s Fund

estimates that some 11 million children in eastern and southern Africa face hunger, disease, and water shortages as a result of the strongest El Niño weather phenomenon in decades. Many scientists believe that El Niño events, caused by warming in the Pacific, are becoming more intense as a result of climate change.

Getting the price of carbon right

Nations from around the world have gathered in Paris for the United Nations Climate Change Conference, COP-21, with the goal of a universal and potentially legally binding agreement on reducing greenhouse gas emissions. We need very broad participation to address fully the global “tragedy of the commons” that results when countries fail to take into account the negative impact of their carbon emissions on the rest of the world. Moreover, free riding by non-participants, if sufficiently widespread, can undermine the political will to action of participating countries.

The nations participating at COP-21 are focusing on quantitative emissions-reduction commitments (the

Intended Nationally Determined Contribution, or INDCs). Economic reasoning shows that the least expensive way for each country to implement its INDC is to put a price on carbon emissions. The reason is that when carbon is priced, those emissions reductions that are least costly to implement will happen first. The IMF

calculates that countries can generate substantial fiscal revenues—revenues that would allow lower distorting taxes and new investments in the economy—by eliminating fossil fuel subsidies and levying carbon charges that capture the domestic damages caused by emissions. A tax on upstream carbon sources is one easy way to put a price on carbon emissions, although some countries may wish to use other methods, such as emissions trading schemes.

Countries that implement their INDCs through a domestic carbon price will reach their goals at lowest cost to themselves, but without global coordination on carbon prices, the cost to the world economy of whatever aggregate emissions reduction is achieved will be unnecessarily high. In order to maximize global welfare, every country’s carbon pricing should reflect not only the purely domestic damages from emissions (for example, health effects of the particulates associated with

burning coal), but also the

damages to foreign countries.

Setting the right carbon price will therefore

efficiently align the costs paid by carbon users with the true social opportunity cost of using carbon. By raising relative demand for clean energy sources, a carbon price would also help to align the market return to clean-energy innovation with its social return, spurring the refinement of existing technologies and the development of new ones. And it would raise the demand for mitigation technologies such as carbon capture and storage, spurring their further development. If not corrected by the appropriate carbon price, low fossil fuel prices are not accurately signaling to markets the true social profitability of clean energy. While alternative estimates of the damages from carbon emissions differ, and it is especially hard to reckon the likely costs of possible catastrophic climate events, most estimates suggest substantial negative effects.

Direct subsidies to R&D have been adopted by some governments but are a poor substitute for a carbon price: they do only part of the job, leaving in place market incentives to over-use fossil fuels and thereby add to the stock of atmospheric greenhouse gases without regard to the collateral costs.

Politically, low oil prices may provide an opportune moment to eliminate subsidies and introduce carbon prices that could gradually rise over time toward efficient levels. However, it is probably unrealistic to aim for the full optimal price in one go. Global carbon pricing will have important redistributive implications, both across and within countries, and these call for gradual implementation, complemented by mitigating and adaptive measures that shield the most vulnerable.

The hope is that the success of the Paris conference opens the door to future international agreement on carbon prices. Agreement on an international carbon-price floor would be a good starting point in that process. Failure to address comprehensively the problem of greenhouse gas emissions, however, exposes all generations, present and future, to incalculable risks.